VIOLENCE IN QUEER PARTNERSHIPS

In November 2014 BBC News published an article stating that domestic violence is more common in same-sex relationships than in heterosexual relationships according to a study conducted in the United States. Why did the researchers come to that conclusion?

To fully address the topic let’s first understand what violence is in general, specifically domestic violence, and how important it is to singl out this term from among the types of violence and have special laws to prevent it.

Domestic violence in simple terms is violence committed by a former or current family member or partner against the other one, a violation of constitutional rights and freedoms. According to the domestic legislation of the Republic of Armenia there are 5 types of domestic violence: physical, sexual, psychological, economical and neglect.

This law as stated in the article aims to ensure the special protection of the family as a natural and basic unit of the society, to create the necessary legal frameworks for the prevention of domestic violence, the safety and protection of victims of domestic violence, their rights and legal interests, etc. (see the whole article).

A question automatically arises within the scope of this topic: how are the cases of domestic violence regulated in the case of a queer partnership? Registration of same-sex marriages is prohibited in Armenia, accordingly the law cannot include these couples.

Domestic violence is a problem that can affect people of any age, sex, sexual orientation and gender identity but there are particularities of the problem that are specific to queer families. These include homophobia, transphobia, internalized homophobia and transphobia, the stigma as a result of association with HIV and AIDS, the risk of STIs, the lack of inclusiveness or absence of legal/legislative protection mechanisms, and of course the psychological violence the queer relationships face from the outside being considered as less “serious” than the heterosexual couples and families.

Here we have another problem: the issue of violence in queer partnerships has not been researched as comprehensively as that of heterosexual relationships, therefore, the existing studies may contradict each other to some extent. Some say that there is more violence in queer partnerships than in heterosexual families, others say that the reason here is the higher rates of recourse of queer partners to protection of the law.

However, the fact is that the problem exists, and there is an experience of legal changes in the world that helps to understand it, bring it up and provide a solution, and it is the experience we will build on here today.

For example, let’s study the experience of the USA.

For example, let’s study the experience of the USA.

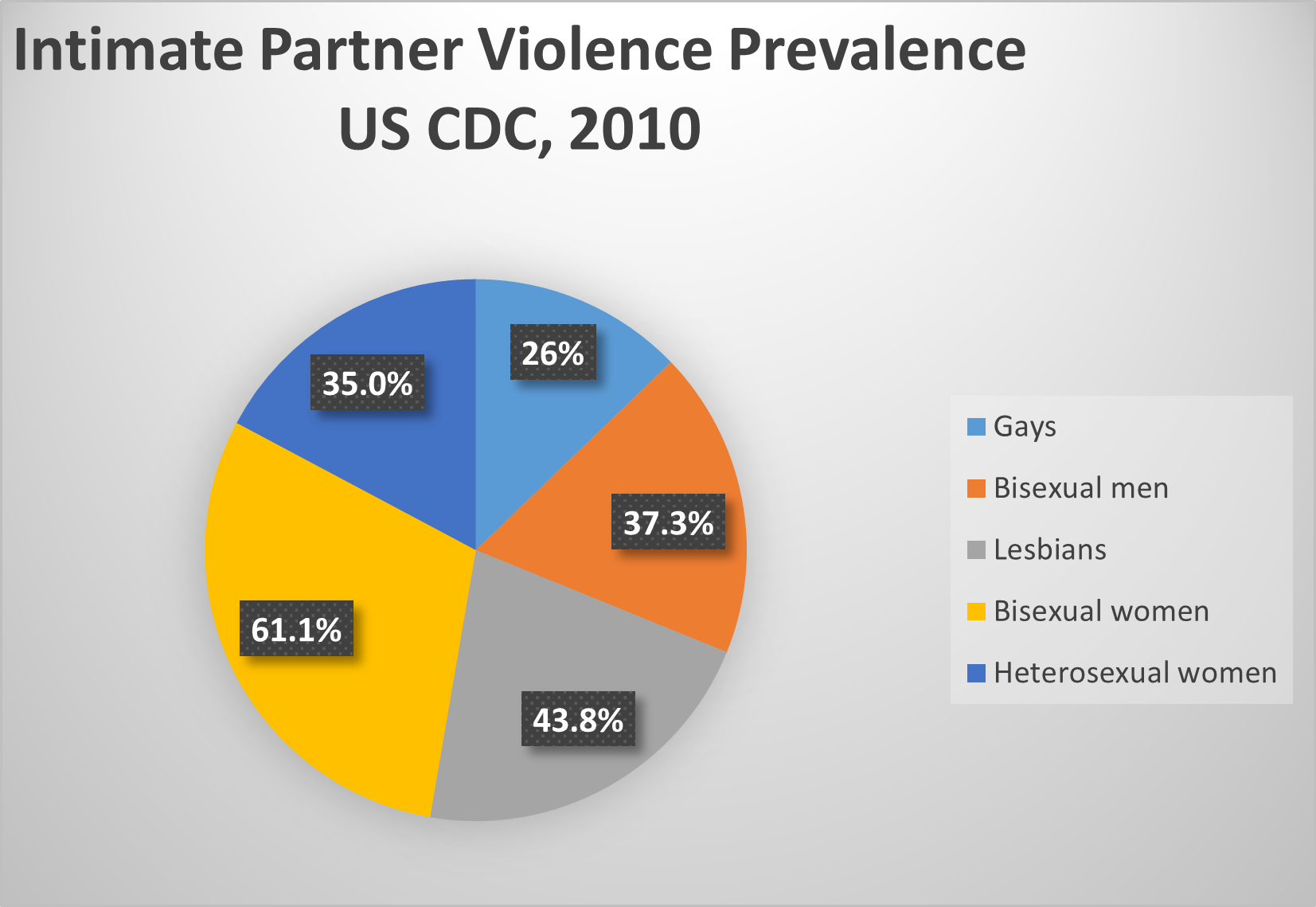

In the study of US National Center for Injury Prevention and Control and Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2010 about Intimate Partner Violence in the United States, 26% of gay men and 37.3% of bisexual men reported they had been physically abused, stalked or raped by their partners, 90.7% and 78.5% (respectively) of which were men. This problem has started to be recorded in Armenia as well. Most recently a gay person who had been abused by his partner applied to New Generation Humanitarian NGO for support. When they used to live together, his partner forced him to provide sexual services to other people and took the earnings. The case is ongoing.

As for lesbians, the CDC states that 43.8% of them reported being physically abused, harassed, or raped by their partners. However, the study notes that only 2/3 (67.4%) of those 43.8% abusers were female (as some lesbian women may have had heterosexual relationships before coming out, which also has its psychological reasons and explanations). The same survey found that 35% of heterosexual women and 61.1% of bisexual women reported physical abuse, stalking or rape by their partners, 98.7% and 89.5% of which (respectively) were men.

According to this research both in the case of men and of women, in general bisexual people experienced violence in relationships more than lesbians and gays. This is also linked to the situation that bisexual people are less understood and are often discriminated against because of their sexual orientation, being considered “non-oriented” even within the community and by organizations that provide relevant assistance.

Relatively less research has been conducted on this issue among trans* people. As we know, gender identity has nothing to do with sexual orientation, so trans* people can be heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or of any other orientation.

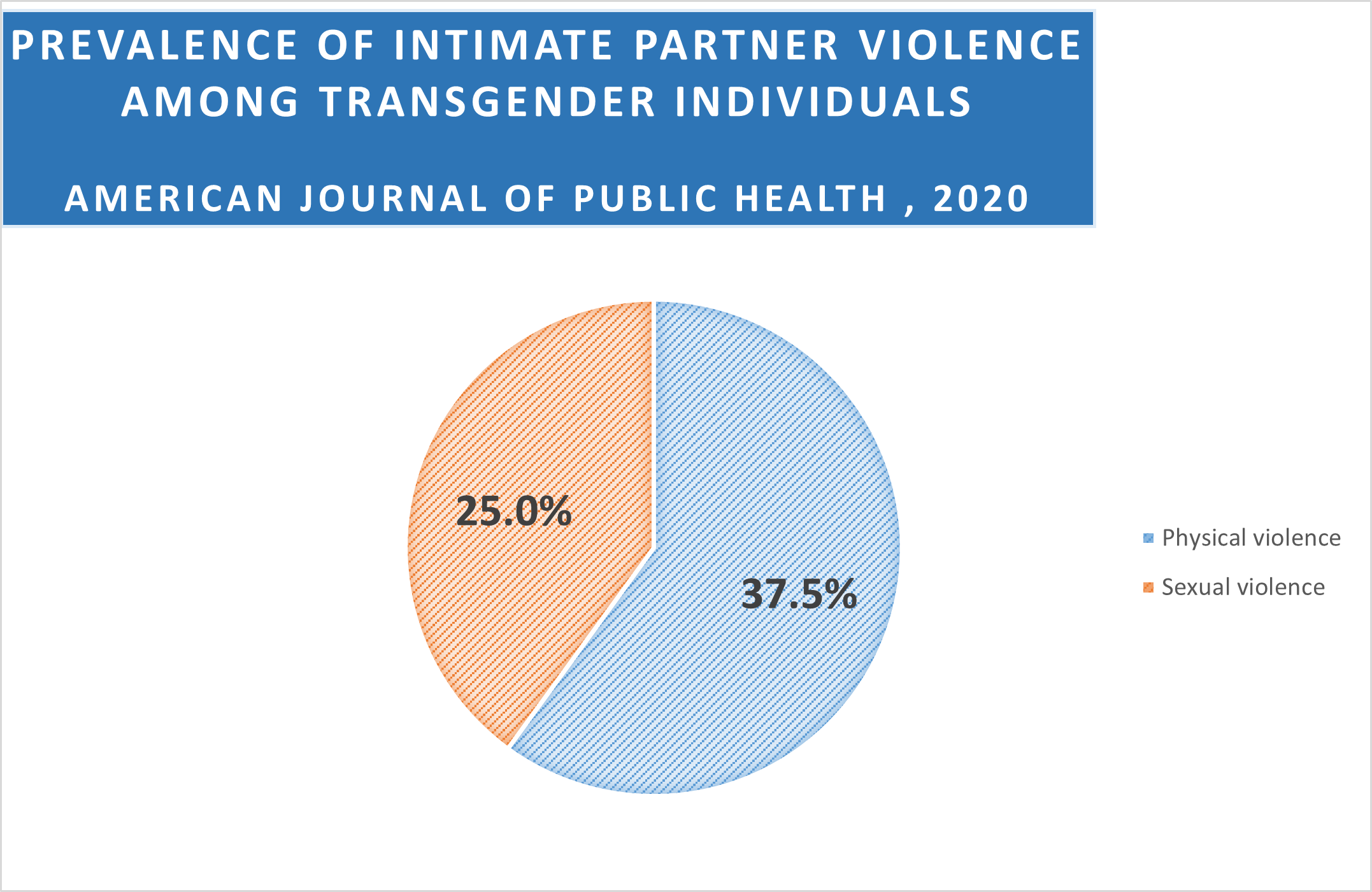

In 2020, the American Journal of Public Health reviewed 85 journal articles to determine the prevalence of intimate partner violence among transgender individuals. On average 37.5% of transgender people reported being physically abused and 25% reported being sexually abused by a current or former partner. In other words, as compared to cisgender people, violence against transgender people committed by their sexual partners is definitely more common.

In 2020, the American Journal of Public Health reviewed 85 journal articles to determine the prevalence of intimate partner violence among transgender individuals. On average 37.5% of transgender people reported being physically abused and 25% reported being sexually abused by a current or former partner. In other words, as compared to cisgender people, violence against transgender people committed by their sexual partners is definitely more common.

Now let’s get back to our main issue.

Queer couples often have difficulty accessing legal protection and assistance because domestic violence laws in many countries are designed to only cover cisgender heterosexual relationships.

And so the above-mentioned BBC article is based on a conclusion made by the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, which in its turn is based on four different studies, with a total of about 30,000 participants interviewed.

“One of our startling findings was that rates of domestic violence among same-sex couples is pretty consistently higher than for opposite sex couples,” says Richard Carroll, a psychologist and co-author of the report. Intrigued by their findings, Carroll’s team started to look into the reasons why this might be.

“We found evidence that supports the minority stress model – the idea that being part of a minority creates additional stress,” Carroll says.

“There are external stressors, like discrimination and violence against gays, and there are internal stressors, such as internalised negative attitudes about homosexuality.”

But it is the internal stress, says Carroll, which can be particularly damaging. “Sometimes homosexual individuals project their negative beliefs and feelings about themselves onto their partner,” he says, adding, “Conversely, we believe that victims of domestic violence in same-sex couples believe, at some level, they deserve the violence because of internalized negative beliefs about themselves.”

As noted in another article, for queer couples, the abuse against each other in their partnership can often be associated with the violence coming from the outside world based on their sexual orientation or gender identity. Therefore, the inner feeling of guilt can prevent one from recognizing the problem and looking for solutions.

Here, it is worth mentioning another important psychological factor: at least ⅓ of the victims of violence tend to commit violence in adulthood. Victims of abuse often respond to the trauma by denying that the abuse happened or by blaming themselves and justifying the abuser’s actions, and as a result, they may not realize how they themselves are turning into abusers over time. Considering society’s attitude towards queer people, it is not difficult to see the whole picture.

Statistics show that 43% of transgender youth are bullied at school, also 29% of them, 21% of lesbians and gays and 22% of bisexuals have attempted suicide, compared to heterosexual cisgender children the percentage of which is only 7%.

16% of gays and lesbians, 11% of bisexuals were threatened or injured with a weapon on the school premises. 29% of gay and lesbian youth and 31% of bisexual youth have been bullied at school, compared to 17% of heterosexuals. We leave the conclusions to the reader.

Violence in queer families is still difficult to talk about. Even while writing this article, when we tried to contact several representatives of the Armenian community and ask them about their experience, when they heard the topic, everyone’s first reaction was the same: there is no violence in queer couples.

This leads us to a simple conclusion that if the problem is not spoken up, it may often go unrecognized, people may not realize what is happening to them or their acquaintances, and may not know how to react to it.

If you, too, think that you have never seen violence in queer partnerships, then answer a simple question: how many times have you heard about partners threatening your queer acquaintances with outing* to their parents, relatives, acquaintances or at their workplace?

I’m sure many times, as outing is a convenient method of manipulation and control for abusers. So isn’t this a psychological violence?

outing* – the act of disclosing a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity without their consent.

Author Anya Hayrapetyan

The article was written within the framework of the project on Domestic Violence in Queer Partnerships implemented by New Generation Humanitarian NGO with financial support of the Foreign Ministry of the Federal Republic of Germany, Civil Society Cooperation and Quarteera e.V. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed herein are those of the Author and do not necessarily reflect those of New Generation Humanitarian NGO, the Foreign Ministry of the Federal Republic of Germany, Civil Society Cooperation or Quarteera e.V.